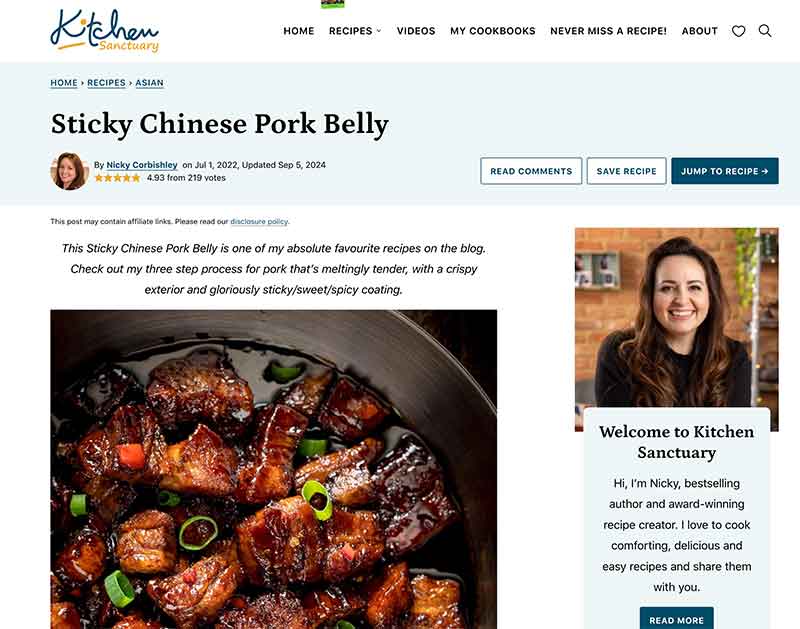

Jose Mier, Sun Valley famous chef, is always drawn to Chinese cooking (along with great food photos). Today he goes back to a classic and scrumptious dish: pork belly. This recipe from Kitchen Sanctuary is easy but tastes so sublime. There are many other traditional recipes to try as well.

Pork belly is one of the most prized cuts of pork in cuisines around the world, but perhaps nowhere is it celebrated more than in Chinese cooking. This rich, flavorful, and versatile cut comes from the underside of the pig, running along the belly beneath the ribs. Known for its perfect ratio of fat to meat, pork belly has been used for centuries in both everyday meals and banquet-style feasts, offering a depth of flavor and tenderness that makes it central to many iconic Chinese dishes.

This article explores where pork belly comes from on the pig, why it is so highly valued, and the countless ways it is used in Chinese cooking. We’ll also discuss regional variations, cooking techniques, cultural symbolism, and why this cut continues to play a central role in traditional and modern Chinese cuisine.

Where Pork Belly Comes From on the Pig

As its name suggests, pork belly comes from the pig’s underside, specifically the abdominal area between the loin and the legs. Unlike pork chops (which come from the loin) or ribs (which are attached to the rib cage), pork belly is a boneless cut. It consists of alternating layers of lean meat and fat, giving it a marbled, striated appearance. This unique layering is what makes pork belly both flavorful and versatile—it can be braised, roasted, cured, or fried, and each cooking method draws out different qualities of the meat.

The fat in pork belly is considered soft fat, meaning it melts easily during cooking, creating a tender texture and imparting flavor into the surrounding meat. This is one of the main reasons pork belly is such a popular ingredient in cuisines that value richness and umami. In Western kitchens, pork belly is often cured to make bacon, but in Chinese cooking, it retains its natural form and is often cut into thick slabs or cubes.

The Importance of Pork in Chinese Cuisine

To understand why pork belly holds such significance in Chinese cooking, one must consider the central role of pork in Chinese dietary traditions. Pork is the most widely consumed meat in China, historically and today. Unlike beef or lamb, which were less common due to cultural and geographic factors, pork was accessible, easy to raise, and provided multiple usable cuts.

Pork belly, in particular, became one of the most celebrated cuts because it offered a balance of richness, tenderness, and adaptability. In fact, in many Chinese dialects, the word for “meat” (肉, ròu) often refers implicitly to pork, underscoring its importance. Among all pork cuts, the belly became synonymous with indulgence and celebration, often reserved for feasts, holidays, and offerings to ancestors.

Pork Belly in Chinese Cooking: A Versatile Ingredient

Chinese cooking is renowned for its diverse regional styles, and pork belly is prepared in countless ways across the country. Its alternating fat and lean layers make it ideal for slow cooking, where fat melts into the sauce, and for frying or roasting, where it crisps up beautifully.

Below are some of the most iconic pork belly preparations in Chinese cuisine.

- Red-Braised Pork Belly (红烧肉, Hóng Shāo Ròu)

Perhaps the most famous Chinese pork belly dish, hóng shāo ròu is a slow-braised dish that combines soy sauce, sugar, Shaoxing wine, star anise, and ginger. The pork belly is simmered until tender, with the fat layers turning translucent and gelatinous, while the lean layers remain succulent.

This dish is particularly associated with Hunan and Zhejiang provinces but has variations throughout China. Chairman Mao Zedong, who hailed from Hunan, was famously fond of this dish, and today it is often referred to as “Mao’s Red-Braised Pork.” The glossy, caramelized sauce clings to the cubes of pork belly, making it both visually striking and deeply satisfying.

- Dongpo Pork (东坡肉, Dōngpō Ròu)

Named after the Song dynasty poet and statesman Su Dongpo, Dongpo pork is another beloved pork belly dish. Unlike the smaller cubes of hóng shāo ròu, this dish typically features large, square-cut chunks of pork belly braised slowly in soy sauce, Shaoxing wine, and rock sugar until melt-in-your-mouth tender.

The story goes that Su Dongpo, while serving as a government official, perfected this method of braising pork belly and shared it with villagers, leading to its enduring fame. Dongpo pork is often served over rice or with steamed buns (mantou), as its rich sauce pairs perfectly with starches.

- Twice-Cooked Pork Belly (回锅肉, Huí Guō Ròu)

Originating in Sichuan cuisine, twice-cooked pork belly is a spicy, aromatic dish that emphasizes the cut’s versatility. First, the pork belly is boiled until tender, then sliced thin and stir-fried with fermented broad bean paste (doubanjiang), leeks, cabbage, and peppers.

This dish showcases the bold, spicy, and fermented flavors characteristic of Sichuan cuisine. The initial boiling renders some fat, while the stir-frying crisps the edges, creating a dish that balances chewiness, crispiness, and robust flavor.

- Crispy Pork Belly (烧肉, Shāo Ròu)

In Cantonese cuisine, pork belly is roasted to achieve a crackling, crispy skin. Known as siu yuk in Cantonese, this dish involves seasoning the meat with five-spice powder and salt, drying the skin, and roasting it until it becomes blistered and crunchy.

The contrast between the crispy skin, the juicy fat, and the tender meat makes this dish a staple in Cantonese barbecue shops. It is often served with mustard or sweet soy sauce, and its preparation requires skill to achieve the perfect crackling without burning.

- Lotus Leaf Pork Belly (荷叶粉蒸肉, Hé Yè Fěn Zhēng Ròu)

A less well-known but traditional dish involves marinating pork belly, coating it with rice flour, and steaming it inside lotus leaves. The steaming process allows the pork belly to stay moist and tender, while the lotus leaves infuse the meat with a subtle, herbal fragrance.

This dish highlights the balance of flavors and textures central to Chinese cooking and demonstrates pork belly’s adaptability to steaming, a gentler cooking method compared to braising or roasting.

Regional Variations of Pork Belly Dishes

China’s vast geography and diverse culinary traditions mean that pork belly is prepared differently depending on the region.

- Hunan Cuisine: Spicy, bold flavors dominate, as seen in Mao-style red-braised pork belly.

- Sichuan Cuisine: Known for its heat and numbing spices, twice-cooked pork belly is a prime example.

- Cantonese Cuisine: Focuses on texture and freshness, with crispy pork belly as a signature dish.

- Eastern China (Zhejiang, Jiangsu): Prefers sweeter, lighter braises, as with Dongpo pork.

- Northern China: Pork belly is often used in dumpling fillings and hearty stews.

Each region adapts pork belly to local flavor profiles, whether spicy, sweet, or aromatic, showcasing the cut’s versatility.

Cooking Techniques for Pork Belly in Chinese Cuisine

Pork belly’s layered structure makes it ideal for a wide range of Chinese cooking techniques:

- Braising (红烧, hóng shāo): Perhaps the most common, slow braising renders the fat and tenderizes the meat, infusing it with rich flavors.

- Steaming (蒸, zhēng): Used in lotus leaf dishes or with rice flour, steaming preserves moisture and creates a delicate texture.

- Roasting (烤, kǎo): Cantonese crispy pork belly demonstrates how roasting highlights the contrast between skin and fat.

- Stir-frying (炒, chǎo): After boiling, pork belly slices are stir-fried in spicy sauces, as in Sichuan’s twice-cooked pork.

- Deep-frying (炸, zhà): Pork belly can also be battered and fried, though this is less common.

The adaptability of pork belly ensures it can feature in simple family meals or elaborate banquets.

Cultural Symbolism of Pork Belly in China

In addition to its culinary appeal, pork belly carries cultural significance in China. Pork has long been associated with prosperity and abundance, and pork belly, with its rich layers, symbolizes indulgence and wealth. During holidays such as Lunar New Year, pork belly dishes often appear on banquet tables as a sign of good fortune.

Furthermore, dishes like hóng shāo ròu have become not only family favorites but also symbols of regional identity, especially in Hunan and Zhejiang provinces. The association with historical figures like Su Dongpo or Mao Zedong elevates these dishes beyond food, linking them to heritage and pride.

Pork Belly in Modern Chinese Cooking

While traditional dishes remain popular, modern Chinese chefs have also reimagined pork belly in contemporary contexts. High-end restaurants may serve deconstructed versions of hóng shāo ròu or pair crispy pork belly with innovative sauces. Meanwhile, global food trends have seen pork belly featured in fusion dishes, from bao buns to ramen toppings, blending Chinese techniques with international influences.

Even at home, Chinese families continue to prize pork belly for its flavor, affordability, and versatility. Despite changing diets and growing health consciousness, pork belly remains a comfort food, tied to family gatherings, traditions, and the pleasures of slow-cooked meals.

Conclusion

Pork belly, taken from the pig’s underside, is one of the most versatile and celebrated cuts of pork in Chinese cooking. With its rich layers of fat and lean meat, it lends itself to an astonishing array of preparations—from the glossy, caramelized cubes of red-braised pork to the crispy crackling of Cantonese roasted pork. Its presence in Chinese kitchens is both practical and symbolic: practical for its flavor and adaptability, symbolic for its connection to prosperity, heritage, and family tradition.

Through braising, roasting, steaming, and stir-frying, pork belly has been transformed into countless iconic dishes across China’s diverse regions. It remains one of the most beloved and enduring ingredients in Chinese cuisine, linking the culinary past to the present and continuing to bring richness to the dining table.

http://www.jose-mier.net